Building Billion-Scale Vector Search - part two

Photo by Julien Tromeur on Unsplash

This blog is the second post in a series on building a billion-scale vector search using Vespa. The series covers the cost and serving performance tradeoffs related to approximate nearest neighbor search at a large scale. In the first post, we introduced some challenges related to building large-scale vector search solutions. We presented these observations made over the years, working on billion-scale vector search systems:

- Surprisingly, many organizations have a lot of raw unstructured data, petabytes of data that easily reach billions of rows.

- AI models to generate vector representations from this data have become a commodity, thanks to Huggingface.

- Few organizations have Google’s level of query traffic searching the data.

- Few organizations need query serving latency much lower than the blink of an eye.

- Query volume fluctuates daily, and pre-provisioning compute resources for peak query traffic wastes resources.

These observations impact our design for a cost-efficient billion-scale vector search solution.

Dataset

This blog post delves into these observations and how we think about implementing large-scale vector search without breaking the bank.

This work is also published as an

open-source Vespa sample application

if you want to jump ahead. To demonstrate, we needed a large-scale vector dataset, and thankfully,

the LAION team released the LAION-5B dataset earlier this year.

The LAION-5B dataset is built from crawled data from the Internet, and the dataset has

been used to train popular text-to-image models like StableDiffusion.

The LAION-5B dataset consists of the following:

- The caption text of the image.

- The URL of the image.

- A 64bit signed hash calculated over the caption text and URL concatenation.

- The height and width of the image.

- NSFW (Not safe for work) labels, labels assigned by a machine-learned NSFW classifier.

- A 768-dimensional vector representation of the image, obtained by running the image data through a multimodal encoding model (CLIP).

We have previously released open-source Vespa sample applications using CLIP models for text-to-image search;

see the blog post and

Vespa sample application for text-to-image search

and text-to-video search.

Those sample applications are great building blocks for powerful multimodal search applications,

but they do not demonstrate scale.

The LAION-5B dataset, on the other hand, offers scale and pre-computed image embeddings with metadata,

and we thought this work would make a great addition to the rich set of Vespa sample applications.

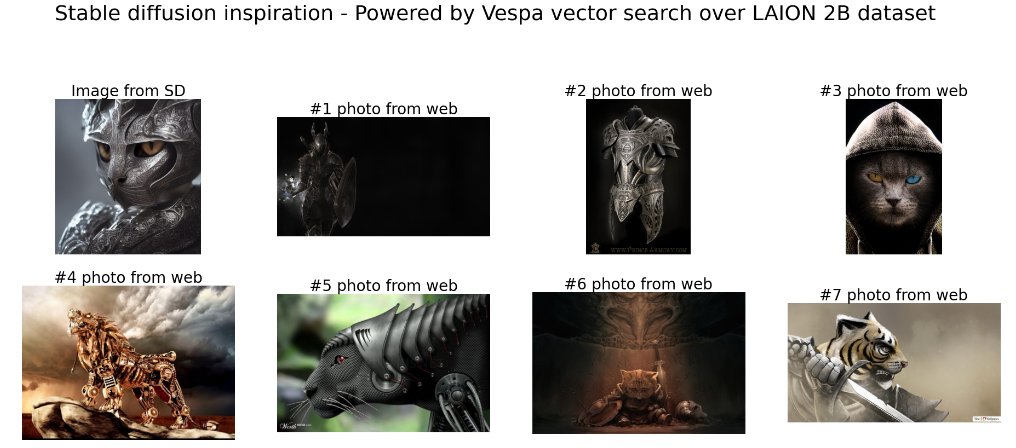

There is a growing interest in generative text-to-image models and also controversy

around the data they are trained on. Where do these models find inspiration from? What about copyrights?

These are questions that many ask. Therefore, building an open, searchable multi-modal index over the

LAION-5B dataset is particularly interesting, given the current controversy.

The top-left image is generated by StableDiffusion, the image is encoded using CLIP, and the vector representation

is used to search the Vespa LAION-5B index using approximate nearest neighbor search.

The top-left image is generated by StableDiffusion, the image is encoded using CLIP, and the vector representation

is used to search the Vespa LAION-5B index using approximate nearest neighbor search.

Search features

This work allows searching both the metadata and the image CLIP embeddings using hybrid search, combining sparse and dense vector representations. We wanted to implement the following core features:

- Search the caption text or URL for keywords or phrases using the full-fledged Vespa query language. For example, select caption, url from image where url contains “https://www.erinhanson.com/”.

- Given a text prompt, encode the text into CLIP embedding space, and use this embedding to search over the CLIP embedding vectors in the

LAION-5Bdataset. - Given an image, encode the image into CLIP embedding space, and use this embedding to search over the CLIP embedding vectors in the

LAION-5Bdataset. For example, given an image generated byStableDiffusion, search for similar images in the training set (LAION). - Hybrid combinations of the above, including filtering on metadata like

NSFWlabels or aesthetic scores.

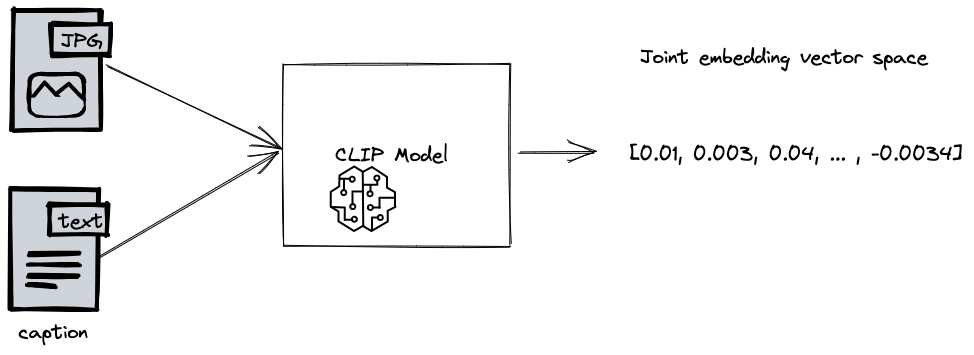

CLIP (Contrastive Language–Image Pre-training). CLIP is trained with captions and image data, inputting pairs at the same time.

At inference (after training), we can input an image, or a text prompt, independently, and get back a vector representation.

CLIP (Contrastive Language–Image Pre-training). CLIP is trained with captions and image data, inputting pairs at the same time.

At inference (after training), we can input an image, or a text prompt, independently, and get back a vector representation.

In addition to the mentioned features, we want to have the ability to update the index. The ability to efficiently update an index, without having to re-build the entire index saves resources and cost, but also enable important functionality. For example, updating aesthetic score, where aesthetic score can be used when ranking images for a text query, either as a hard filter, or as a ranking signal.

Designing a cost-efficient large-scale vector search solution

In a previous blog post, we presented a hybrid approximate nearest search algorithm

combining HNSW with an Inverted file so that the majority of the vector data could be stored on disk,

which due to storage hierarchy economics, is at least one order of magnitude cheaper than in-memory graph representations.

In another post, we covered coarse-level approximate nearest neighbor search

methods where the vectors are compressed, for example, using binary representations in

combination with bitwise hamming distance

to perform an efficient but coarse-level search, and where full precision vectors were paged on-demand from disk for re-scoring.

In this work, implementing search use cases over the LAION-5B dataset,

we wanted to combine multiple approximate vector search techniques discussed in previous blog posts.

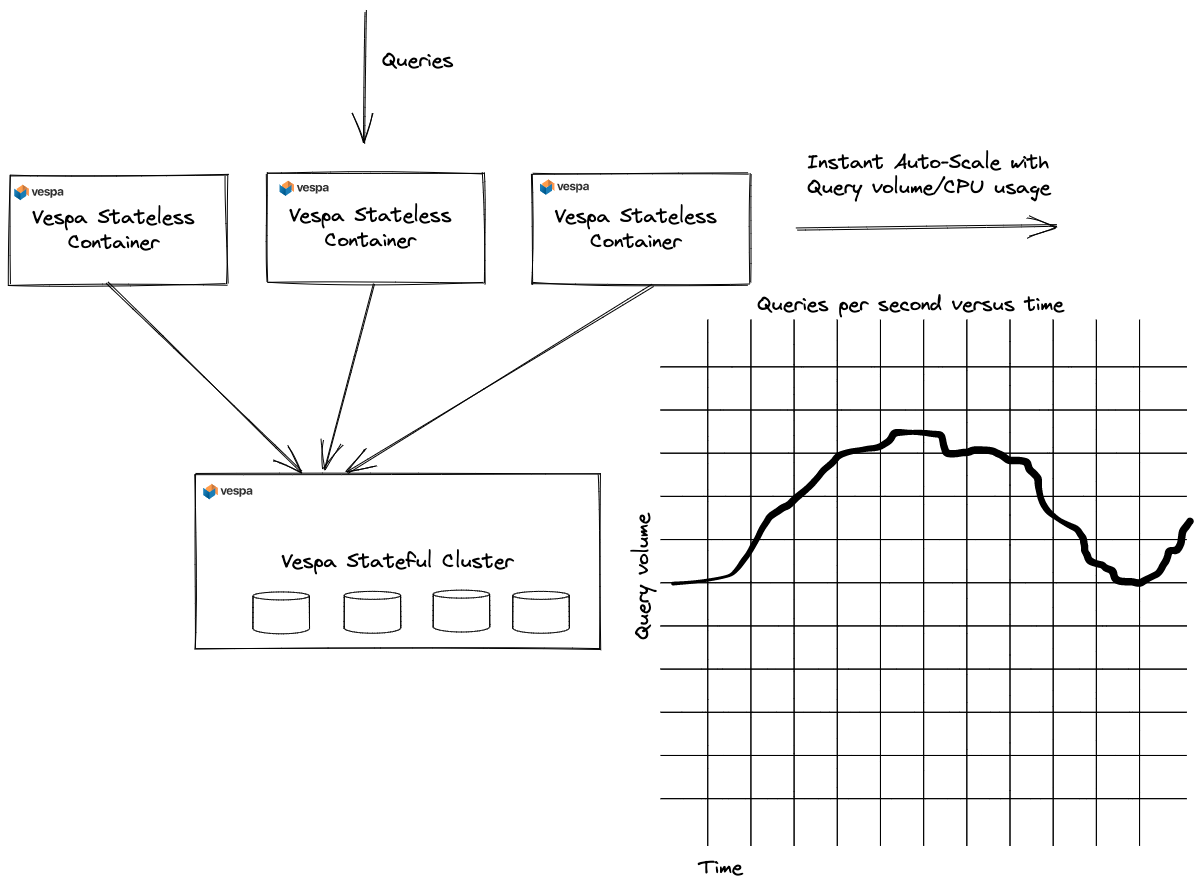

Additionally, we wanted to move parts of vector similarity computations out of the Vespa content clusters to stateless

clusters, for faster auto-scaling with query volume changes 1.

Relaxing latency requirements from single-digit milliseconds to double-digits, enables moving vector similarity calculations out of Vespa stateful nodes to stateless container nodes. This then also enable faster auto-scaling of stateless resources with changes in query volume1. In the cloud, where resources can be provisioned on-demand within seconds, paying for idle resources at low user traffic is wasteful and costly.

To scale at ease with query traffic changes, we need to move vector similarity computations

to the Vespa stateless container layer and move vector data on-demand, efficiently across the network from content clusters to stateless container clusters.

This also meant that we need a way to perform a first-phase similarity search close to the data on the content nodes

so that the stateless containers could work on a small subset of the vector dataset.

Without an efficient first-phase candidate coarse selection, we would need to move too much vector data per query across the network.

This would hurt serving latency and quickly run into network bandwidth bottlenecks at high query throughput.

This tiered compute approach, where smaller and computationally efficient models are applied close to the data, is used in many real-world search and recommendation use cases, known as multi-phase retrieval and ranking. Effectively, a distributed search operation falls under the MapReduce paradigm, where the map compute stage is pushed close to the data, avoiding moving data across the network. The reducer stage operates on a much smaller amount of data, which is suitable for transferring across the network.

Hybrid HNSW-IF with PCA

The hybrid HNSW-Inverted-File method, described in detail in Billion-scale vector search using hybrid HNSW-IF, uses clustering or random centroid selection to identify centroids that span the high-dimensional vector space. Centroids are indexed using Vespa’s support for HNSW indexing, allowing efficiently searching 100s of millions of centroids on a single instance with single digit milliseconds, single-threaded.

With Vespa’s support for distributed search, the centroid content cluster storing and indexing the centroids can be scaled to billions of centroids, unlocking indexing trillion-sized vector datasets. Separating the centroid graph into a dedicated content cluster enables using memory-optimized instance types without needing locally attached disks, further optimizing the deployment cost.

Vectors from the real-world dataset are assigned a set of close centroids at indexing time and indexed into the inverted file content cluster. The inverted index then maps from a centroid id to the posting list of vectors close to the centroid. Vespa’s inverted indexes are disk-based and memory mapped.

In our previous work using HNSW-IF with a static vector dataset containing vectors without any metadata,

we split the dataset into two, centroids and non-centroids,

using the same Vespa document schema with a field to differentiate the two classes.

This work diverges from that approach and instead represents centroids as a

separate Vespa document schema. This has several benefits for real-world datasets:

- The centroid representation can use fewer dimensions than the original embedding representation.

For example, using vector quantization or other dimension-reduction techniques.

Centroids are indexed using

HNSW, and dimension reduction reduces the memory footprint and increases the number of centroids that can be indexed per instance type (memory resource constraints). We can fit 6x more centroids per node for any instance type if we reduce the vector dimensionality from 768 to 128. Additionally, vector similarity computations enjoy a similar speedup when reducing the number of dimensions. - Centroids are separated from the original vector dataset, and centroids are never deleted.

Since the number of centroids is very large, compared to other

InvertedFilemethods, we expect to be able to incrementally index new image data without having to redo the centroid selection.

Dimension reduction using Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

Our implementation uses a separate Vespa document schema to represent centroids, enabling the use of dimension reduction for the centroid vectors. The intuition behind this idea is that the centroid search is a coarse search. For example, in a 2-dimensional geographical longitude and latitude vector space, we can quickly focus on the grid coordinates to our point of interest before doing the fine-level search.

A technique for performing dimension reduction is

principal component analysis (PCA).

We train a PCA matrix (128x768) using a small subset (10%) of the vector dataset. This step is performed offline.

This dimension reduction technique fits well with the Vespa architecture, and we perform the PCA matrix multiplication during

the stateless processing of queries and documents. This step is implemented as a simple

stateless component.

The matrix multiplication between the incoming vector and the trained PCA matrix is accelerated

using Vespa’s support for accelerated inference with ONNX-Runtime.

The PCA matrix weights are stored in an ONNX model imported into the Vespa application package.

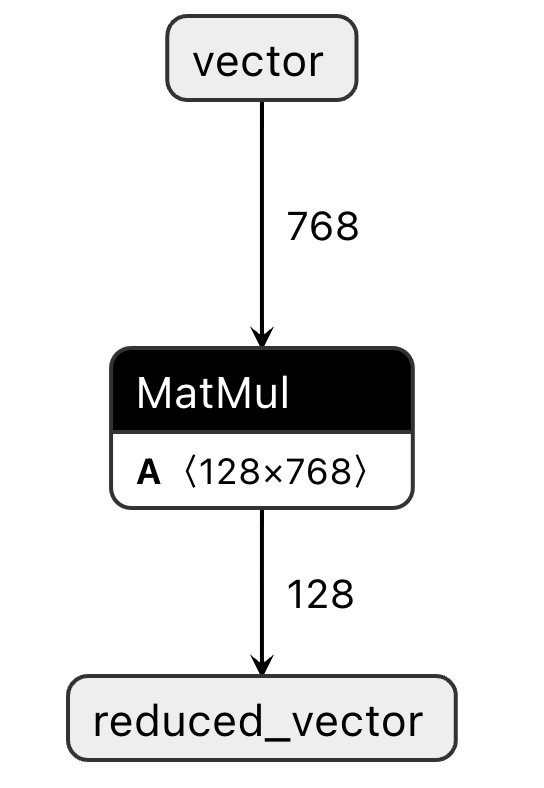

The ONNX compute graph visualization is given below. The input is a 768-dimensional vector,

and the output is a reduced 128-dimensional vector.

PCA matrix multiplication for dimension reduction. The A matrix represents the trained PCA matrix weights.

After using dimension reduction for centroids to lower the memory footprint of the HNSW graph,

we realized that we could also use dimension reduction for the image embedding vectors,

using the reduced vector space for a coarse-level first-phase ranking.

- At query time, we reduce the query vector using the same dimension reduction technique and use the reduced query vector representation to search the HNSW graph for close centroids. After this first stage, we have a list of K centroid ids.

- We dispatch a new query to the image content cluster, searching for the list of centroids obtained from the previous stage.

- Each image content node ranks the images using

innerproductin the reduced vector space. - After obtaining the global top N images, ranked in the reduced vector space, we can request the full vector representation and perform re-ranking in the original vector space.

By implementing a coarse-level ranking of the images retrieved by the centroid search,

we can limit the number of full-precision vectors needed for innerproduct calculations in

the original 768-dimensional vector space. This tiered compute approach is

a classic example of tried and tested phased retrieval and ranking.

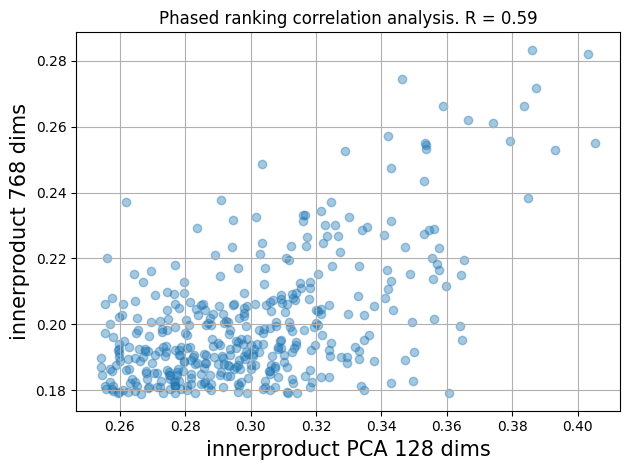

With phased ranking, we want the two ranking phases to correlate; a high innerproduct score in the PCA reduced

vector space should also produce a high innerproduct score in the original vector space. If there is weak correlation,

the overall quality becomes very sensitive to the re-ranking depth.

Correlation analysis between the innerproduct in the PCA-reduced space versus the innerproduct in the original space

The above simple scatter plot with Pearson correlation coefficient, gives us a visualization and also confirmation that our two ranking phases do correlate. There are multiple different ways to calculate the correlation between ranked lists:

Centroid Selection and Centroid Schema

A signed 32-bit hash of the vector representation is used to represent the centroid document id.

Since the LAION dataset has many image duplicates, hashing avoids storing the same vector point multiple times in the HNSW graph.

We randomly pick about 10% of the vectors from the original dataset to represent centroids.

schema centroid {

document centroid {

field id type int {}

field reduced_vector type tensor<bfloat16>(x[128]) {

indexing: attribute | index

index {

hnsw {

max-links-per-node: 24

neighbors-to-explore-at-insert: 200

}

}

attribute {

distance-metric: innerproduct

}

}

}

rank-profile default {

num-threads-per-search: 1

inputs {

query(q_reduced) tensor<float>(x[128])

}

first-phase {

expression: closeness(field, reduced_vector)

}

match-features: attribute(id) closeness(field, reduced_vector)

}

}

The centroid schema only defines two fields, the hashed identifier (id) and the

dimension-reduced centroid vector representation (reduced_vector) using 128 dimensions.

Generally, bfloat16 saves 50% of storage compared to float precision without significant accuracy loss.

The distance metric used is innerproduct which we can use since we are working on normalized vectors. The chosen HNSW indexing hyper-parameters provide a reasonable tradeoff between centroid search accuracy, memory usage, and search complexity.

LAION Image Schema

The image schema representing the rows in the LAION dataset is given below.

See the full version

in the schemas directory of the release sample application.

schema image {

document image {

field language type string {

indexing: "en" | set_language

}

field url type string {

indexing: summary | index

}

field caption type string {

indexing: summary | index

}

field height type int { .. }

field width type int { .. }

field centroids type array<string> { .. }

field reduced_vector type tensor<bfloat16>(x[128]) {

indexing: attribute

attribute: paged

}

field vector type tensor<bfloat16>(x[768]) {

indexing: summary

}

}

fieldset default {

fields: caption, url

}

document-summary vector-summary {

from-disk

summary vector type tensor<bfloat16>(x[768]) {

source: vector

}

}

rank-profile default {

inputs {

query(q) tensor<float>(x[768])

query(q_reduced) tensor<float>(x[128])

}

first-phase {

expression: sum(query(q_reduced) * attribute(reduced_vector))

}

match-features: firstPhase

}

}

The LAION metadata fields, like url, caption, and height/width, are self-explanatory.

These fields use Vespa’s support for regular text matching with indexing:index, supporting keyword search and ranking,

and advanced query operators like phrase, near, onear and more.

An un-scoped prompt text search, searching the default fieldset,

will search across both the url and the caption.

- The

centroidsfield stores and indexes the k closest centroid ids (in the reduced space). This field is populated during document processing by searching the centroid cluster. - The

reduced_vectoris the result of the PCA dimension reduction projection. The reduced vector uses the attribute paged option, which means that Vespa does not lock the data into memory but leaves it to the OS to cache frequently accessed vectors. - The full-precision (

bfloat16) 768-dimensional CLIP vector is only stored, specified byindexing: summary. Fields defined only withsummary, withoutindexorattribute, cannot be used for retrieval and ranking at the content nodes. The summary data is compressed and stored in the Vespa summary log store. - The vector-summary

document-summaryallows stateless searcher components to request only the vector data for an image result from the content nodes. Explicit document summaries reduce network footprint and serialization-related computational costs. - Ranking, the

rank-profiledefaultspecifies thefirst-phaseranking expression, which is theclosenessrank feature, which calculates theinnerproductin the reduced vector space.

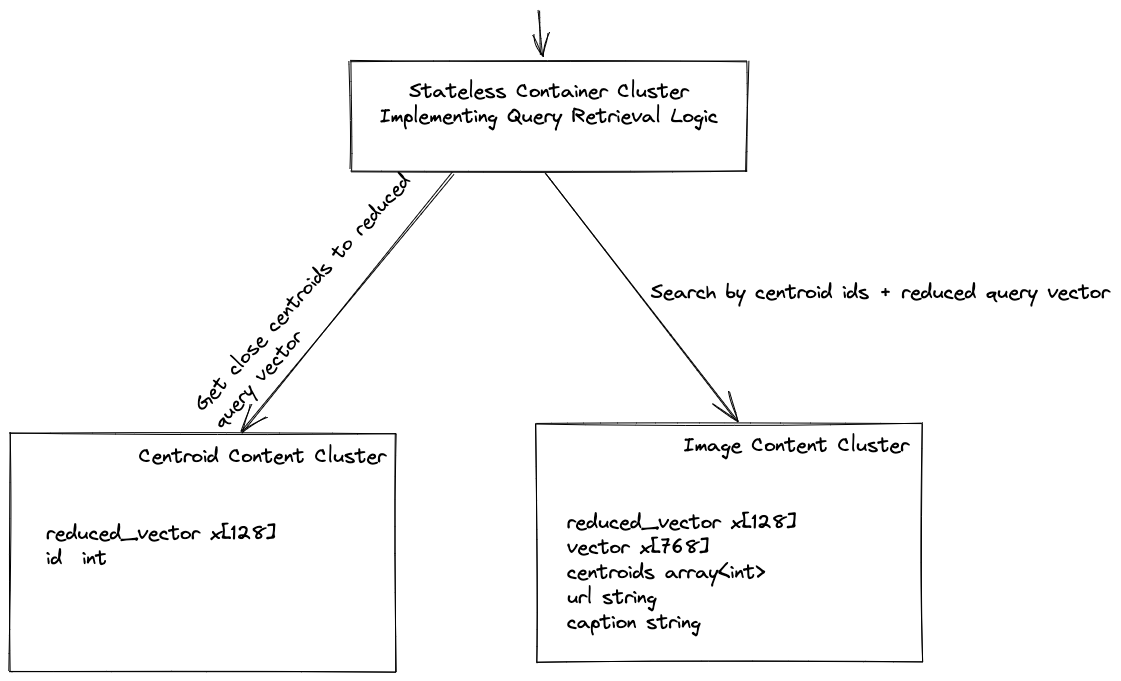

Illustration of schemas and content clusters. Separating the centroid and image schema into separate content clusters, allow for choosing optimal instance types for the workload.

Stateless container re-ranking

We have, in previous sections, introduced the centroid and image schemas, coarse-level centroid retrieval,

and image similarity ranking in the dimension-reduced vector space.

The coarse-level search and ranking are performed on each of the content nodes in the image content cluster,

but we want to add another ranking stage, run after the top-k closest vectors in the reduced space is found.

We need to add a stateless component implementing re-ranking using the full precision vector representation.

A Vespa query is executed in at least two protocol phases:

- Find the matching documents executing the schema configurable ranking.

- Fetch the summary data of the top-k best documents after merging the result of the matching phase.

Below is an example of a stateless searcher implementation that performs global re-ranking over the top 1000 hits.

public class RankingSearcher extends Searcher {

@Override

public Result search(Query query, Execution execution) {

int userHits = query.getHits();

query.setHits(1000)

Result result = execution.search(query);

ensureFilled(result, "vector-summary", execution);

reRank(result)

result.hits().sort()

result.hits().trim(0, userHits)

return result;

}

}

The searcher illustrates the event-driven flow of a stateless searcher component doing top-k re-ranking.

In this case, the middle-tier (or user) has requested query.getHits() hits.

The searcher increases the number of hits to 1K and executes the search,

which can include other searchers in a chained execution, eventually reaching the content nodes,

which execute the ranking configured in the schema.

After execution.search(query), we have a list of hits ranked by the content nodes.

However, to save network bandwidth (potentially hundreds or even thousands of nodes involved in the query),

the hits data does not contain the summary data — we need to fetch the field contents

before we can start accessing field-level hit data. This is done in the ensureFilled(result, "vector-summary", execution) stage.

In this case, we use an optional document summary vector-data. An explicit document-summary reduces network

traffic, serialization, and deserialization cost. The Vespa internal search and fill protocols between stateless containers and stateful content nodes are

based on Protocol Buffers over RPC,

avoiding serialization and deserialization overheads.

To perform the reRank phase, we turn to Vespa’s support for

accelerated model inference using stateless model evaluation

powered by ONNX-Runtime.

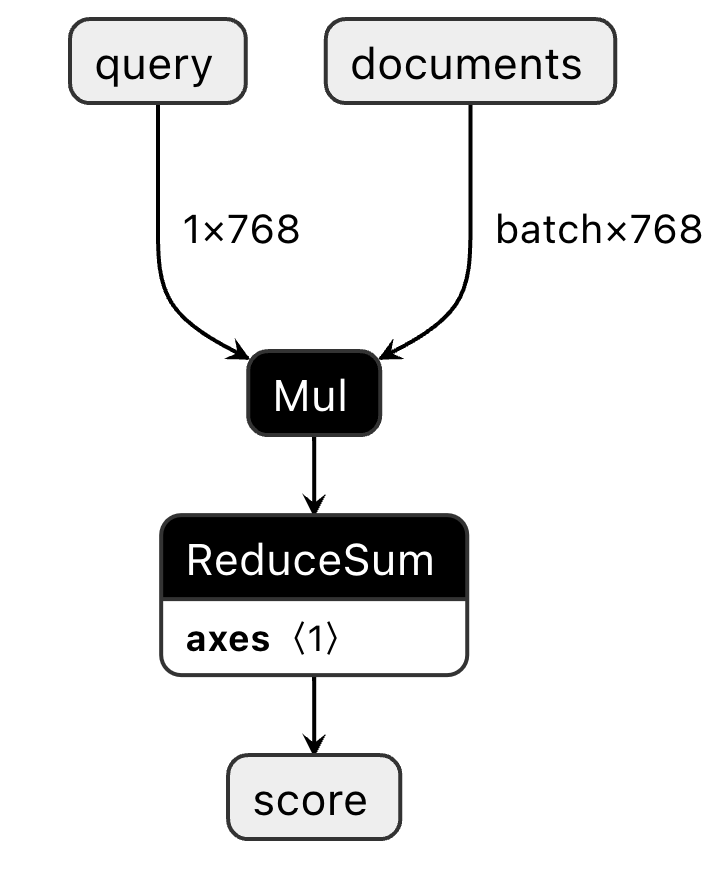

ONNX Compute Graph - input is a single query vector of 768 dimensions and a batch of document vectors, also 768 dimensions

After evaluating the ranking model, all we need to do is to update the hit score and re-sort the hits. See RankingSearcher for the detailed implementation.

By moving the final ranking stage to the stateless container nodes, we move a significant portion of the computing out of the content and storage layer, and we can quickly scale stateless resources with changes in query volume.

Summary

In this post, we looked at design choices when implementing a cost-efficient search solution for the LAION-5B dataset.

- We introduced dimension reduction with

PCA, used to reduce the memory footprint of the centroid indexing withHNSW. - Compute tiering or phased ranking. By performing a similarity search in the reduced vector space as a coarse-level search, we lower the computational complexity of similarity calculations performed close to the data on the content nodes.

- Stateless re-ranking, moving the majority of the similarity computations to stateless containers, allowing for faster auto-scaling with query volume fluctuations.

If you want to start building your copy of the LAION-5B index, you can already try out

our billion-scale-image-search sample application.

In the next post in this series, we look at query serving performance, integrating the CLIP encoder into the Vespa stateless container cluster,

and how we improve the quality of results by performing query-time diversification using image-to-image similarity. Stay tuned for more cat photos.

Footnotes

-

Stateful Vespa content clusters can be auto-scaled with the document or traffic volumes. Still, doubling or ten-folding capacity to handle query traffic changes requires moving and activating (indexing) data across more nodes or adding or removing replicas (Vespa groups). Activating across more replicas or groups for stateful systems is more resource-intensive (and time-consuming) than scaling stateless resources. ↩ ↩2