Building Billion-Scale Vector Search - part one

Photo by Arnaud Mariat on Unsplash

How fast is fast? Many consider the blink of an eye, around 100-250ms, to be plenty fast. Try blinking 10 times in a second? If you can manage, your blink of an eye latency is around 100ms. But did you know that algorithms and data structures for approximate vector search can search across billions of vectors in high dimensional space in a few milliseconds?

In this blog post, we look at how fast is fast enough in the context of vector search, and how the answer to this question impacts how we design and build a billion-scale vector search solution.

Introduction

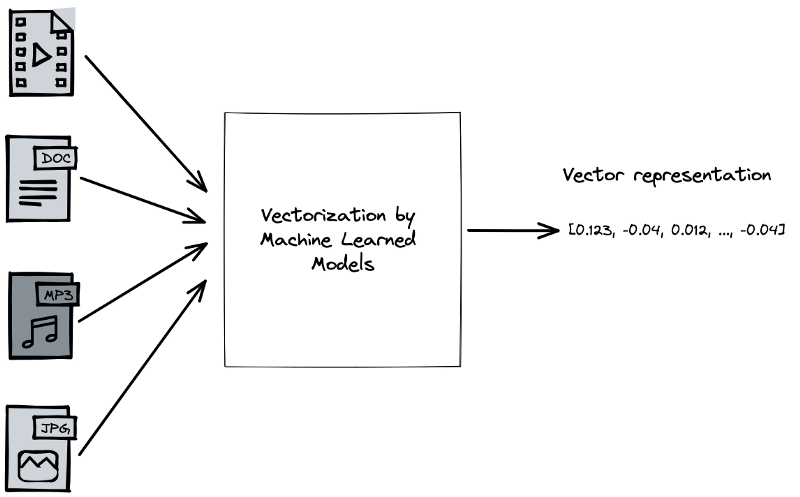

Advances in self-supervised deep learning have revolutionized information extraction from unstructured data like text, audio, image, and [videos](https://ai.facebook.com/blog/generative-ai-text-to-video/. In addition to these modalities, multimodality models are on the rise, combining multiple modalities, for example, text and image data. These advances in deep learning leading to better vector representations of data have driven increased interest in searching these representations at scale.

Any machine learning algorithm must transform the input and output data into a data format the machine understands. This is where vectors and, generally, tensors come into the picture.

Everything can be represented as a vector in high-dimensional vector space

Using mentioned ML models, we can convert our data into vectors and index the vectors using an algorithm for nearest neighbor search. Given a query, for example, a picture, a text document, a search query, or dating preferences, we can convert it into a vector representation using the same model we used to index our collection. Then, we can use this representation to search for similar data in the collection using vector search in the high dimensional vector space.

Searching over a few million vector representations is trivial as the index can fit into a single instance. There is much tooling for searching small amounts of vector data, where all the data can serve in a single node. We can replicate the index over more nodes if we need to scale query throughput. However, we need to distribute the data over multiple nodes with more data.

More data, more problems

Building out real-time serving infrastructure for searching over billion-scale or trillion-scale vector datasets is one of the most challenging problems in computing and has been reserved for FAANG-sized organizations. When the data no longers fit into a single instance, data must be distributed over multiple serving instances. With more instances come failure modes. The serving system needs to implement resilience for failures, distributed search over an elastic number of partitions, and replication to avoid losing data in case of failures.

More data and more problems are reflected by the high pricing of cloud-based vector search solutions. In addition, the pricing tells a story of the infrastructure complexity and market demand for fully managed cloud-based vector search solutions.

For example, suppose your organization wants to index 1B 512-dimensional vectors using Google Vertex AI Matching Engine. In that case, you’ll be adding $389,000 per month to your GCP cloud bill. That quote example is for one batch job of vectors. Each new batch indexing job adds $6,000. The quote does not cover storing the data that produced the vectors; that data must be served out of a different serving store.

Building cost-efficient large-scale vector search

Over the past few years, we have made a few observations around scaling vector search to billions of data items:

- Surprisingly, many organizations have a lot of raw unstructured data, petabytes of data that easily reach billions of rows.

- AI models to generate vector representations from this data have become a commodity, thanks to Huggingface.

- Few organizations have Google’s level of query traffic searching the data.

- Few organizations need query serving latency much lower than the blink of an eye 1.

- Query volume changes and pre-provisioning resources for peak query traffic wastes resources.

These observations impact our design for a cost-efficient billion-scale vector search solution.

The quickest and most accurate methods for approximate nearest neighbors search (ANNS) use in-memory data structures. For example, the popular HNSW graph algorithm for ANNS requires storing the vectors in memory for low latency access during query and indexing. In 2022, many cloud providers will offer cloud instance types with large amounts of memory, but these types also come with many v-CPUs, which drives costs. These high-memory and high-compute instance types support massive queries per second. They might be the optimal instance type for applications needing to support large query throughput with high accuracy. However, as we have observed, many real-world applications do not need enormous query throughput but still need to search sizeable billion-scale vector datasets with relatively low latency with high accuracy.

Due to these tradeoffs, there is an increasing interest in hybrid ANNS algorithms using solid-state disks (SSD) to store most of the vector data combined with in-memory graph data structures. Storing the data on disk lowers costs significantly due to storage hierarchy economics. Furthermore, 2022 cloud instances come with higher network bandwidth than we have used to. The higher bandwidth allows us to move more data from content nodes to stateless compute nodes. In addition, independent scaling of content and compute enables on-demand, elastic auto-scaling of resources.

Vespa’s value proposition

Vespa, the open-source big data serving engine, makes it straightforward for an any-sized organization to implement large-scale search and recommendation use cases. The following Vespa primitives are the foundational building blocks for building a vector search serving system.

Document Schema(s)

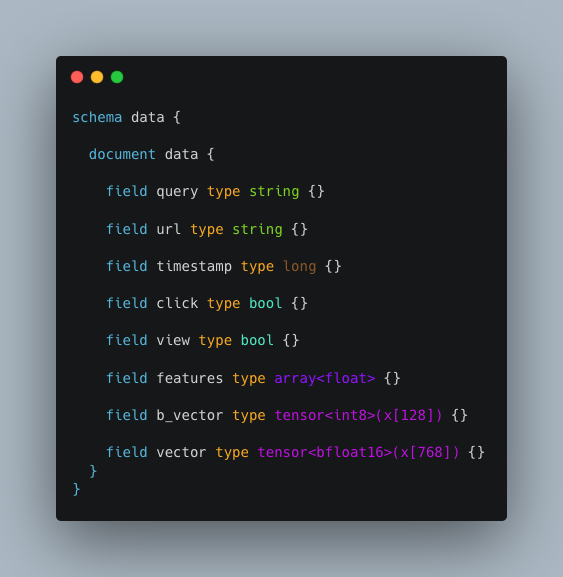

Vespa’s schema model supports structured and unstructured data types, including tensors and vectors. Representing tensors, vectors, and unstructured data types in the same document schema avoids consistency and synchronization issues between data stores.

A simplified Vespa document schema, expressed using Vespa’s schema language.

CRUD (Create, Read, Update, Delete) operations

Add new documents, and update and delete documents using real-time APIs.

Searching structured and unstructured data in the same query request

A feature-rich query language for performing efficient selections over the data. Vespa’s SQL-like query language enables efficient online selection over billions of documents, combining search over structured and unstructured data in the same query.

Efficient Vector Search

Vespa implements a real-time version of the HNSW algorithm for efficient and high-recall ANNS. The implementation is verified with multiple vector datasets on ann-benchmarks.com and used in production by Spotify.

Highly Extensible Architecture

Vespa allows developers to embed custom components for stateless processing, allowing separation of processing from storage content clusters. In addition, support for multiple content clusters allows scaling stateful resources independently.

Summary

In the next blog post in this series, we’ll cover the design and implementation of a cost-efficient billion-scale image search application over multimodal AI-powered CLIP representations. The application uses a hybrid ANN solution where most of the vector data is stored on disk and where the most computationally expensive vector similarity operations are performed in the stateless layer to allow faster, elastic auto-scaling of resources.