Summer Internship at Vespa

Photo generated with Stable Diffusion

This summer, two young men have revolutionized the field of information retrieval! Or at least they tried… Read on for the tale of this year’s summer interns, and see the fruits of our labor in the embedder auto-training sample app.

Automatic Embedder Training with an LLM

Our main project this summer has been developing a system for automatically improving relevance for semantic search. Semantic search utilizes machine-learned text embedders trained on large amounts of annotated data to improve search relevance.

Embedders can be fine-tuned on a specific dataset to improve relevance further for the dataset in question. This requires annotated training data, which traditionally has been created by humans. However, this process is laborious and time-consuming – can it be automated?

Enter large language models! LLMs like ChatGPT have been trained on an enormous amount of data from a multitude of sources, and appear to understand a great deal about the world. Our hypothesis was that it would be possible to use an LLM to generate training data for an embedder.

Query generation

Training data for text embedders used for information retrieval consists of two parts: queries and query relevance judgments (qrels). Qrels indicate which documents are relevant for which queries, and are used for training and to rate retrieval performance during evaluation. Our LLM of choice, ChatGPT (3.5-turbo-4k), works by providing it with a system prompt and a list of messages containing instructions and data. We used the system prompt to inform ChatGPT of its purpose and provide it with rules informing how queries should be generated.

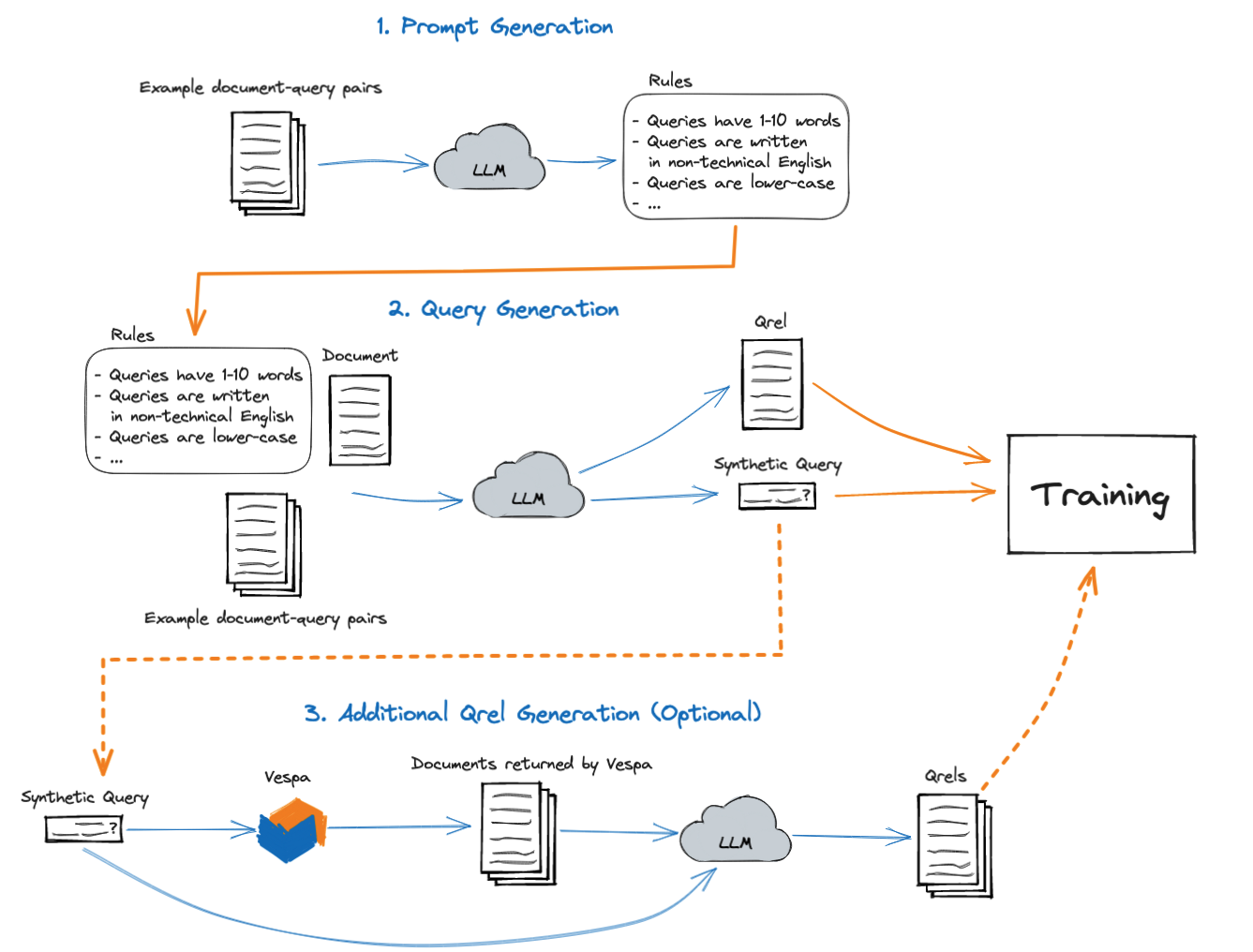

Generating queries requires a system prompt, example document-query pairs, and a document to generate queries for. Our system generates the system prompt, and optionally generates additional qrels, resulting in the three-step process illustrated by the diagram above.

In the beginning, we handcrafted system prompts while trying to get ChatGPT to generate queries similar to existing training data. After some trial and error, we found that we got better results if we specified rules describing what queries should look like. Later, we devised a way for ChatGPT to generate these rules itself, in an effort to automate the process.

Using the system prompt alone did not appear to yield great results, though. ChatGPT would often ignore the prompt and summarize the input documents instead of creating queries for them. To solve this, we used a technique called few-shot prompting. It works by essentially faking a conversation between the user and ChatGPT, showing the LLM how it’s supposed to answer. Using the aforementioned message list, we simply passed the LLM a couple of examples before showing it the document to generate queries for. This increased the quality of the output drastically at the cost of using more tokens.

After generating queries, we optionally generate additional qrels. This can be necessary for training if the generated queries are relevant for multiple documents in the dataset, because the training script assumes that all matched documents not in the qrels aren’t relevant. Generating qrels works by first querying Vespa with a query generated by ChatGPT, then showing the returned documents and the generated query to ChatGPT and asking it to judge whether or not each document is relevant.

Training and evaluation

We utilized SentenceTransformers for training, and we initialized from the E5 model. We started off by using scripts provided by SimLM, which got us up and running quickly, but eventually wanted more control of our training loop.

The training script requires a list of positive (matching) documents and a list of negative (non-matching) documents for each query. The list of positive documents is given by the generated qrels. We assemble a list of negative documents for each query by querying Vespa and marking each returned document not in the qrels as a negative.

After training we evaluated the model with trec_eval and the nDCG@10 metric. The resulting score was compared to previous trainings, and to a baseline evaluation of the model.

We encapsulated the entire training and evaluation procedure into a single Bash script that let us provide the generated queries and qrels as input, and get the evaluation of the trained model as output.

Results

The results we got were varied. We had the most successful training on the NFCorpus dataset, where we consistently got an evaluation higher than the baseline. Interestingly we initially got the highest evaluation when training on just 50 queries! We eventually figured out that this was caused by using the small version of the E5 model – using the base version of the model gave us the highest evaluation when training on 400 queries.

Training on other datasets was unfortunately unsuccessful. We tried training on both the FiQA and the NQ dataset, tweaking various parameters, but weren’t able to get an evaluation higher than their baselines.

Limitations and future work

The results we got for NFCorpus are a promising start, and previous research also shows this method to have promise. The next step is to figure out how to apply our system to datasets other than NFCorpus. There’s a wide variety of different options to try:

- Tweaking various training parameters, e.g. number of epochs and learning rate

- Different training methods, e.g. knowledge distillation

- Determining query relevance with a fine-tuned cross-encoder instead of with ChatGPT-generated qrels

- More data, both in terms of more documents and generating more queries

- Using a different model than E5

We currently make some assumptions about the datasets we train on that don’t always hold. Firstly, we do few-shot prompting when generating queries by fetching examples from existing training data, but this system is perhaps most useful for datasets without that data. Secondly, we use the ir_datasets package to prepare and manage datasets, but ideally we’d want to fetch documents from e.g. Vespa itself.

Most of our training was done on the relatively small NFCorpus dataset because of the need to refeed all documents, after each training, to generate new embeddings. This becomes a big bottleneck on large datasets. Implementing frozen embeddings, which allows reusing document embeddings between trainings, would solve this problem.

Side quests

The easiest way to learn Vespa is to use it. Before starting on the main project, we spent some time trying out the various interactive tutorials. We also worked on various side projects which were related to the main project in some way.

Embedding service

We created a sample app to create embeddings from arbitrary text, using the various models in the Vespa model hub. This was a great way to learn about Vespa’s stateless Java components and how Vespa works in general.

Pyvespa

Pyvespa is a Python API that enables fast prototyping of Vespa applications. Pyvespa is very useful when working in Python, like we did for our machine learning experiments, but it does not support all of Vespa’s features. In addition, there were some issues with how Pyvespa handled certificates that prevented us from using Pyvespa in combination with an app deployed from the Vespa CLI.

We were encouraged to implement fixes for these problems ourselves. Our main changes were to enable Pyvespa to use existing certificates generated with the Vespa CLI, as well as adding a function to deploy an application from disk to Vespa Cloud via Pyvespa, allowing us to use all the features of Vespa from Python (this feature already existed for deploying to Docker, but not for deploying to Vespa Cloud). This was very satisfying, as well as a great learning experience.

Our experience at Vespa

We’ve learned a lot during our summer at Vespa, especially about information retrieval and working with LLMs. We’ve also learned a lot about programming and gotten great insight into the workings of a professional software company.

Contributing to an open-source project, especially such a large one as Vespa, has been very exciting. Vespa is powerful, which is awesome, but as new users, there was quite a lot to take in. The project is well documented, however, and includes a great number of sample apps and example use cases, meaning we were usually able to find out how to solve problems on our own. Whenever we got really stuck, there was always someone to ask and talk to. A big shout out to all of our colleagues, and a special thanks to Kristian Aune and Lester Solbakken for their support and daily follow-up during our internship.

Working at Vespa has been a great experience, and we’ve really enjoyed our time here.